The voice, above all, is that which is lost to the wind. Mafalda Arnauth reminds us of this in a song entitled ‘Esta Voz Que Me Atravessa’ [This Voice That Crosses Me]. The song speaks of a voice that does not live inside the singer but in a shadow beside her. In the second verse she sings, ‘Trago cravado no peito / Um resto de amor desfeito / Que quando eu canto me dói / Que me deixa a voz em ferida’ [I bear, embedded in my chest, / A shard of broken love / That hurts me when I sing / That leaves my voice wounded]. The final verse reveals that the voice that has possessed the singer is in fact that of Maria Severa and did not die with the fadista. The singer is encountering a voice older than she. Here, the voice itself is the site for an acting out of the memory work supposedly undertaken by all fadistas who show fidelity to the originary figure of Severa. The voice becomes an object, like the shawl worn by female fadistas as a sign of mourning for Severa. This object bears none of the claims to originality familiar to so many commentaries on the individuality of the voice; rather, it is collectively owned, something to be taken up, borne and passed on.

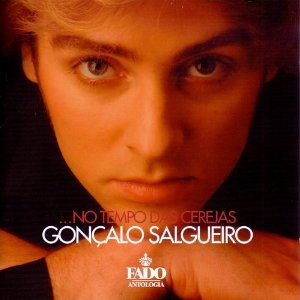

There is a responsibility to fado singing, then, one that permits Mariza to name her first album Fado em Mim [Fado in Me] and to include on it a song explicitly about responsibility, ‘Ó Gente da Minha Terra’ [O People of My Land]. It might be more accurate to say that there is a responsibility to singing in general which fado recognizes. This allows the fadista António Zambujo, for example, to sing ‘Trago Alentejo na Voz’ [I Carry Alentejo in My Voice], in which the carrying of a place and style quite other to that of Lisbon fado can be voiced. Zambujo signals recognition of the polyphonic singing tradition common to the area of Alentejo in the south of Portugal, both in the lyrical message he delivers and in the addition of a male choir to his recording of the song. Another example of this carrying of a responsibility can be found in the work of the fadista Gonçalo Salgueiro, especially his debut album …No Tempo das Cerejas (2002).

The album opens with a song entitled ‘Grito’ [Shout/Cry], a verse written by Amália and set to music by her former guitarist Carlos Gonçalves. Guitarra and viola set the musical scene for around half a minute before falling silent. The word ‘silêncio’ is voiced, stretching over ten otherwise silent seconds, with the majority of work being engaged on the middle vowel as Salgueiro introduces us immediately to his (at first subtle) vocal ornamentation. An audible intake of breath is then followed with the following section of the verse, still unaccompanied by the guitarists and with increasing ornamentation on each word:

The album opens with a song entitled ‘Grito’ [Shout/Cry], a verse written by Amália and set to music by her former guitarist Carlos Gonçalves. Guitarra and viola set the musical scene for around half a minute before falling silent. The word ‘silêncio’ is voiced, stretching over ten otherwise silent seconds, with the majority of work being engaged on the middle vowel as Salgueiro introduces us immediately to his (at first subtle) vocal ornamentation. An audible intake of breath is then followed with the following section of the verse, still unaccompanied by the guitarists and with increasing ornamentation on each word:

Do silêncio faço um grito

E o corpo todo me dói

Deixai-me chorar um pouco[From the silence I make a cry

And my whole body hurts

Leave me to weep a little]

Over the course of the first four lines, and occupying a significant section of the song in terms of duration, we experience what Simon Frith calls ‘the sheer physical pleasure of singing itself … the enjoyment a singer takes in particular movements of muscles’. Furthermore, a message is communicated directly: voice will be central to this recording project. And so it turns out. Following a fairly strident rendition of ‘Meia Noite e uma Guitarra’, a different enjoyment of the voice that complements the subtle intricacy of the album’s opener, the third track comes in the form of a poem written by Maria de Lourdes DeCarvalho with Amália in mind and entitled ‘Tenho em Mim a Voz dum Povo’ [I Have in me Voice of a People]. The poem sings of a ‘Voz com que canto e me encanto / Em cada canto do meu pranto / Uma estranha lágrima de fogo’ [Voice with which I sing and which enchants me / in each song of my lament / A strange tear of fire].

Responsibility is key here. Salgueiro is carrying a responsibility, as the liner notes to the CD make clear. He is in the tradition of Amália and veers, according to Rui Vieira Nery’s version of the singing-as-enjoyment phenomenon, between ‘the joy of risk-taking and a liking for conservatism’. As the accompanying biography alerts us, Salgueiro was invited by João Braga to be part of a show that accompanied the moving of Amália’s body to the National Pantheon in 2001. There is a layering of responsibility here as Salgueiro is given the task of ‘carrying’ Amália in his voice and Amália is given the posthumous responsibility of eternal national recognition. In her third verse, DeCarvalho has Salgueiro speak on behalf of Amália of the latter’s new home alongside the poets Camões and Pessoa, a home that is both the Pantheon itself (the home of mortal remains) and the Infinite in which her ‘eternal soul’ will sing a song in the presence of God.

Responsibility is key here. Salgueiro is carrying a responsibility, as the liner notes to the CD make clear. He is in the tradition of Amália and veers, according to Rui Vieira Nery’s version of the singing-as-enjoyment phenomenon, between ‘the joy of risk-taking and a liking for conservatism’. As the accompanying biography alerts us, Salgueiro was invited by João Braga to be part of a show that accompanied the moving of Amália’s body to the National Pantheon in 2001. There is a layering of responsibility here as Salgueiro is given the task of ‘carrying’ Amália in his voice and Amália is given the posthumous responsibility of eternal national recognition. In her third verse, DeCarvalho has Salgueiro speak on behalf of Amália of the latter’s new home alongside the poets Camões and Pessoa, a home that is both the Pantheon itself (the home of mortal remains) and the Infinite in which her ‘eternal soul’ will sing a song in the presence of God.

This appeal to God should not surprise us. Fado, like other cultural products and processes in Portugal, has deep connections with Catholicism and many of its key tropes (fate, sin, guilt, redemption) could be traced back to religious practices. We can find a fine example of the divine implications of the fado voice in a song written for Amália by Alberto Janes and entitled ‘Foi Deus’ [It Was God]. The song begins, not unlike ‘Tudo Isto É Fado’, with the singer claiming ignorance; in this case it is the reason for the sorrowful tone with which she sings fado of which she is ignorant. But this ignorance is superseded by the declaration that ‘It was God / That placed in my chest / A rosary of pain / For me to speak / And to cry while singing / He made the nightingale a poet / Put rosemary in the fields / Gave flowers to the Spring / Ah, and gave this voice to me’. In one rather simplistic sense, this provides us with an ‘answer’ to a question posed by so many commentators about the ‘magical’ power of Amália’s voice. How did that voice allow her to transcend the politics and traditions of her time and become so ‘universally’ acknowledged? The answer appears that to be that it was not her voice after all but part of God’s plan. In Mafalda Arnauth’s ‘A Voz Que Me Atravessa’ the voice that passed through the singer, while capable of travelling across time and space, had mortal origins in the figure of Maria Severa. Here, the origins are explicitly divine. In one song, we hear the voice of the people; in the other, the voice of God.

Manuela Cook suggests that the fatalism of fado is generally connected to an earlier fatalism found in the Romans and Greeks and is in fact in tension with Catholic faith in which ‘a Christian healing power defies a non-Christian merciless destiny.’ But it is the latter, the ‘omnipotent but merciful God’, that Cook recognizes in Amália’s ‘Foi Deus’ rather than ‘ancient inexorable deities’. Cook’s discussion of the role of women in fado singing covers the witnessing of the Fátima miracle in 1917, offering a useful reminder of the role of witnessing in religious lore. Many different religions place emphasis on witnessing, testifying, performative preaching, ritual and what Simon Frith calls ‘the collective voice of religious submission’.

Notions of submission and possession are frequently given voice in fados such as Maria da Fé’s ‘Cantarei Até Que a Voz Me Doa’ [I Will Sing Until My Voice Hurts]. This song is a speaking-out, or singing-out, a stubborn persistence to make oneself heard and to not have one’s voice lost to the ether. Like ‘A Voz Que Me Atravessa’ and ‘Foi Deus’, it represents a giving of oneself over to the voice and the song. But the reliance on another figure is lessened; neither God nor the mythological fadista are required. The witness here, like the witness in court, is someone who takes the stand and who is given their moment to speak out, licensed by the people to speak for the people. In this sense, it is a very public song and immediately brings to mind visions of its performance in a casa de fado such as the one Maria da Fé herself operates.

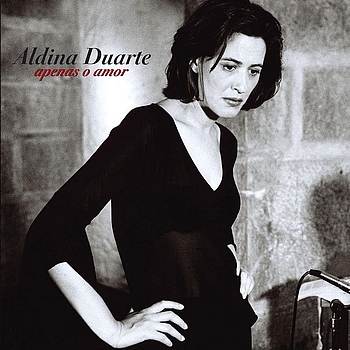

This emphasis on speaking out and on public voices should not distract us from the privacies and intimacies of speaking and listening allowed by sound recording. Aldina Duarte, no stranger to the casa de fado, nonetheless fashioned an intimate form of communication on her first album Apenas o Amor (2004) that could only have come about through the medium of recording. The album is notable for having a sense of sonic intimacy that is attained by the unhurried nature of the arrangements and the way the voice and guitars have been miked and recorded, with a slight echo that serves to emphasize the clean silence surrounding the words and notes. This is further highlighted by songs which reference the affect of voice. The first song begins with the evocation of a ‘voice in the silence’, while the second opens with ‘the memory of a sad voice’; another speaks of ‘an unconscious voice / that deep down is always fado’. On the slower tracks, José Manuel Neto’s guitarra is a model of minimal accompaniment, allowing the voice room to materialize in the sonic field. It is no surprise that fellow musicians Carlos do Carmo and Jorge Palma, who both provide liner notes to the album, speak of silence in their comments.

This emphasis on speaking out and on public voices should not distract us from the privacies and intimacies of speaking and listening allowed by sound recording. Aldina Duarte, no stranger to the casa de fado, nonetheless fashioned an intimate form of communication on her first album Apenas o Amor (2004) that could only have come about through the medium of recording. The album is notable for having a sense of sonic intimacy that is attained by the unhurried nature of the arrangements and the way the voice and guitars have been miked and recorded, with a slight echo that serves to emphasize the clean silence surrounding the words and notes. This is further highlighted by songs which reference the affect of voice. The first song begins with the evocation of a ‘voice in the silence’, while the second opens with ‘the memory of a sad voice’; another speaks of ‘an unconscious voice / that deep down is always fado’. On the slower tracks, José Manuel Neto’s guitarra is a model of minimal accompaniment, allowing the voice room to materialize in the sonic field. It is no surprise that fellow musicians Carlos do Carmo and Jorge Palma, who both provide liner notes to the album, speak of silence in their comments.

As Simon Frith writes, ‘The microphone made it possible for singers to make musical sounds – soft sounds, close sounds – that had not really been heard before in terms of public performance … [it] allowed us to hear people in ways that normally implied intimacy – the whisper, the caress, the murmur.’ This intimacy is hymned in Alexandre O’Neil’s ‘Há Palavras Que Nos Beijam’ [There Are Words That Kiss Us], a poem that has been performed as a fado by Mariza and Cristina Branco. Meanwhile, the ‘memória duma voz triste’ that Aldina Duarte sings about also suggests a carrying on the part of the listener too, a reminder that in listening something is placed in the mind, becoming a part of consciousness itself

Maria da Fé & Ana Moura, ‘Divino Fado’

Mísia, for her part, chose to revisit the song on her 2001 album Ritual, having already recorded a version for her second album in 1993. Where the

Mísia, for her part, chose to revisit the song on her 2001 album Ritual, having already recorded a version for her second album in 1993. Where the  A glance through the part of Amália’s

A glance through the part of Amália’s  It was Amália’s simultaneous ability to court these poets while remaining free from the persecutions of the Estado Novo that came to infuriate many people and that still divides opinion on the singer now. For her critics, Amália’s political naivety smacked too much of the populism peddled by Salazar himself; this was hardly helped by the fact that fado and Amália had become synonymous and that, as fado now became tarred through association with the old regime, so, many felt, should its foremost proponent. This, allied to the sheer excitement of the new forms of music springing up in the wake of the canto de intervenção movement and imported Anglo-American rock music, helped to push fado out of the spotlight in the early days of democracy. Yet fado did not go away and neither did Amália, though her career took a definite downward turn within Portugal for a few years. It was during this period that Carlos do Carmo emerged as the new lantern bearer of fado. Less politically naive than Amália, Carmo brought a commitment to the ideas of the Revolution together with love, deep knowledge and experience of fado gained from his mother, the famous fadista Lucília do Carmo, and from the fado house he inherited from his father. Carmo worked frequently with the poet José Carlos Ary dos Santos and attempted, like Rodrigues and Afonso before him, to bridge the music of the city with that of the countryside. His most notable achievements in this respect were the albums Um Homem na Cidade (1977) and Um Homem no Pais (1983), built upon Santos’s lyrics.

It was Amália’s simultaneous ability to court these poets while remaining free from the persecutions of the Estado Novo that came to infuriate many people and that still divides opinion on the singer now. For her critics, Amália’s political naivety smacked too much of the populism peddled by Salazar himself; this was hardly helped by the fact that fado and Amália had become synonymous and that, as fado now became tarred through association with the old regime, so, many felt, should its foremost proponent. This, allied to the sheer excitement of the new forms of music springing up in the wake of the canto de intervenção movement and imported Anglo-American rock music, helped to push fado out of the spotlight in the early days of democracy. Yet fado did not go away and neither did Amália, though her career took a definite downward turn within Portugal for a few years. It was during this period that Carlos do Carmo emerged as the new lantern bearer of fado. Less politically naive than Amália, Carmo brought a commitment to the ideas of the Revolution together with love, deep knowledge and experience of fado gained from his mother, the famous fadista Lucília do Carmo, and from the fado house he inherited from his father. Carmo worked frequently with the poet José Carlos Ary dos Santos and attempted, like Rodrigues and Afonso before him, to bridge the music of the city with that of the countryside. His most notable achievements in this respect were the albums Um Homem na Cidade (1977) and Um Homem no Pais (1983), built upon Santos’s lyrics. When Amália did return it was in triumph, performing to packed houses and initiating a new series of recordings which, though they would often veer towards the gimmicky, nonetheless paved the way for her powerful albums of self-written material at the beginning of the 1980s. It is perhaps worth considering Geoffrey O’Brien’s discussion of the return of Burt Bacharach in the 1990s when considering both Amália’s post-Revolution comeback and her audience’s willingness to re-embrace her. The songwriting process that Bacharach and his colleagues symbolize is comparable to the creative process of fado canção, which can be seen as the driving force behind the musical period covered in Fado and the Place of Longing. Like Rodrigues’s ‘classic’ period, Bacharach’s period was one of professionals – a Hollywood-style division of labour – as opposed to the singer-songwriter style that would come to dominate afterwards; O’Brien describes the process as ‘a combination of perfectionism and commercialism’. Eduardo Sucena’s

When Amália did return it was in triumph, performing to packed houses and initiating a new series of recordings which, though they would often veer towards the gimmicky, nonetheless paved the way for her powerful albums of self-written material at the beginning of the 1980s. It is perhaps worth considering Geoffrey O’Brien’s discussion of the return of Burt Bacharach in the 1990s when considering both Amália’s post-Revolution comeback and her audience’s willingness to re-embrace her. The songwriting process that Bacharach and his colleagues symbolize is comparable to the creative process of fado canção, which can be seen as the driving force behind the musical period covered in Fado and the Place of Longing. Like Rodrigues’s ‘classic’ period, Bacharach’s period was one of professionals – a Hollywood-style division of labour – as opposed to the singer-songwriter style that would come to dominate afterwards; O’Brien describes the process as ‘a combination of perfectionism and commercialism’. Eduardo Sucena’s

It is at this same point that fado took on the responsibility of being the professional, ‘official’ Portuguese music of loss (or, as several fadologists would seem to prefer, the music of Portuguese loss, which is saying a rather different thing). Salazar’s policies undoubtedly exacerbated this process of fencing-off but did not create it. As with the emergence of rock ’n’ roll in the United States, there are a number of issues to consider when determining why fado canção emerged when it did and why Amália Rodrigues became its paradigmatic performer, ranging from changes in the law (here, the Novo Estado policies were crucially determinant but previously extant copyright laws should not be forgotten, affecting as they do the role of the artist in the period of mass mediation); migration to the cities; changes in recording and media technology; shifts in the high/low divide in the arts.

It is at this same point that fado took on the responsibility of being the professional, ‘official’ Portuguese music of loss (or, as several fadologists would seem to prefer, the music of Portuguese loss, which is saying a rather different thing). Salazar’s policies undoubtedly exacerbated this process of fencing-off but did not create it. As with the emergence of rock ’n’ roll in the United States, there are a number of issues to consider when determining why fado canção emerged when it did and why Amália Rodrigues became its paradigmatic performer, ranging from changes in the law (here, the Novo Estado policies were crucially determinant but previously extant copyright laws should not be forgotten, affecting as they do the role of the artist in the period of mass mediation); migration to the cities; changes in recording and media technology; shifts in the high/low divide in the arts. Her biographical details resound with references to poverty, to the Mouraria, to singing on the streets while selling fruit, to being discovered in the fado houses and wooed into the world of professional performance and recording, and, ultimately, to living her life in a fog of saudade and permanent unhappiness which no amount of success or fame could shift. The extent to which the development of this persona was deliberate or accidental seems to matter less than the place she came to occupy in the Portuguese imagination.

Her biographical details resound with references to poverty, to the Mouraria, to singing on the streets while selling fruit, to being discovered in the fado houses and wooed into the world of professional performance and recording, and, ultimately, to living her life in a fog of saudade and permanent unhappiness which no amount of success or fame could shift. The extent to which the development of this persona was deliberate or accidental seems to matter less than the place she came to occupy in the Portuguese imagination. By the time Amália took on the role of Maria Severa in a 1955 Lisbon production of Júlio Dantas’s play, she had already surpassed that early fadista in terms of myth and prominence, due mainly to the success she had achieved internationally. While fado had hardly been unknown outside Portugal previously, it had never reached the level of exposure given it by Amália. Now an international star, she found herself being offered ever increasing opportunities, from performances worldwide to cinema roles nationally and in France. She had also demonstrated a strong desire to explore beyond the limits of traditional fado. It had become increasingly popular for fado singers in the 1940s to move away from the rigidly structured verses of the earlier period towards a freer style based on the work of contemporary poets such as Frederico de Brito. In addition to these newer styles of fado canção, Amália recorded other non-fado and folk songs, as well as Spanish flamenco, Mexican rancheras, and French, English and Italian versions of Portuguese songs (most famously ‘Coimbra’, released in an Italian version under the same title and refashioned as ‘Avril au Portugal’ and ‘April in Portugal’ elsewhere). This explorative aspect of Amália’s approach to her music encouraged musicians and songwriters to approach her with new ideas and led to collaborations that were to have an enormous impact on the direction fado would take.

By the time Amália took on the role of Maria Severa in a 1955 Lisbon production of Júlio Dantas’s play, she had already surpassed that early fadista in terms of myth and prominence, due mainly to the success she had achieved internationally. While fado had hardly been unknown outside Portugal previously, it had never reached the level of exposure given it by Amália. Now an international star, she found herself being offered ever increasing opportunities, from performances worldwide to cinema roles nationally and in France. She had also demonstrated a strong desire to explore beyond the limits of traditional fado. It had become increasingly popular for fado singers in the 1940s to move away from the rigidly structured verses of the earlier period towards a freer style based on the work of contemporary poets such as Frederico de Brito. In addition to these newer styles of fado canção, Amália recorded other non-fado and folk songs, as well as Spanish flamenco, Mexican rancheras, and French, English and Italian versions of Portuguese songs (most famously ‘Coimbra’, released in an Italian version under the same title and refashioned as ‘Avril au Portugal’ and ‘April in Portugal’ elsewhere). This explorative aspect of Amália’s approach to her music encouraged musicians and songwriters to approach her with new ideas and led to collaborations that were to have an enormous impact on the direction fado would take. On the musical side it is generally agreed, and was frequently admitted by Amália herself, that it was the collaboration with the pianist and composer Alain Oulman which brought about the most far-reaching revolution in her fado style. What Oulman brought to Amália’s work was an ability to break free of established fado styles though a sophisticated musical language, while maintaining a strong link with the essential elements that kept the music recognizable as fado. Amália would rehearse with Oulman at the piano and he would occasionally accompany her on her recordings alongside the time-honoured guitarra and viola. Oulman’s arrangements allowed a greater variety of poetic styles to be utilized for fado lyrics, a development first brought to the public’s attention on the 1962 album Asas Fechadas, popularly known as Busto after the bust of Amália which adorned the cover.

On the musical side it is generally agreed, and was frequently admitted by Amália herself, that it was the collaboration with the pianist and composer Alain Oulman which brought about the most far-reaching revolution in her fado style. What Oulman brought to Amália’s work was an ability to break free of established fado styles though a sophisticated musical language, while maintaining a strong link with the essential elements that kept the music recognizable as fado. Amália would rehearse with Oulman at the piano and he would occasionally accompany her on her recordings alongside the time-honoured guitarra and viola. Oulman’s arrangements allowed a greater variety of poetic styles to be utilized for fado lyrics, a development first brought to the public’s attention on the 1962 album Asas Fechadas, popularly known as Busto after the bust of Amália which adorned the cover. Of the nine tracks on the album seven have music written by Oulman. The lyrics are provided by Rodrigues herself (the famous ‘Estranha Forma de Vida’) and by the poets Luís de Macedo, Pedro Homem de Melo and, mostly, David Mourão-Ferreira, whose 1960 collection À Guitarra e à Viola had been dedicated to Amália and contained the verses for ‘Aves Agoirentas’ ‘Madrugada de Alfama’, ‘Maria Lisboa’ and the political fado ‘Abandono’, all included on Busto. Rodrigues and Oulman also collaborated on the work of less contemporary poets; 1965 saw the release of the EP ‘Amália Canta Camões’ and the album Fado Português, the former containing three adaptations of Portugal’s national poet, the latter harbouring one of the Camões pieces, as well as a cantiga de amigo credited to the medieval troubadour Mendinho, and the title song based on José Régio’s poem, alongside work by Mourão-Ferreira, Homem de Melo and Macedo.

Of the nine tracks on the album seven have music written by Oulman. The lyrics are provided by Rodrigues herself (the famous ‘Estranha Forma de Vida’) and by the poets Luís de Macedo, Pedro Homem de Melo and, mostly, David Mourão-Ferreira, whose 1960 collection À Guitarra e à Viola had been dedicated to Amália and contained the verses for ‘Aves Agoirentas’ ‘Madrugada de Alfama’, ‘Maria Lisboa’ and the political fado ‘Abandono’, all included on Busto. Rodrigues and Oulman also collaborated on the work of less contemporary poets; 1965 saw the release of the EP ‘Amália Canta Camões’ and the album Fado Português, the former containing three adaptations of Portugal’s national poet, the latter harbouring one of the Camões pieces, as well as a cantiga de amigo credited to the medieval troubadour Mendinho, and the title song based on José Régio’s poem, alongside work by Mourão-Ferreira, Homem de Melo and Macedo.